This text was originally prepared for Educational Services Australia and published on the Scootle Lounge, and has been modified to suit this post.

(Image credit: A photo by Denny Luan)

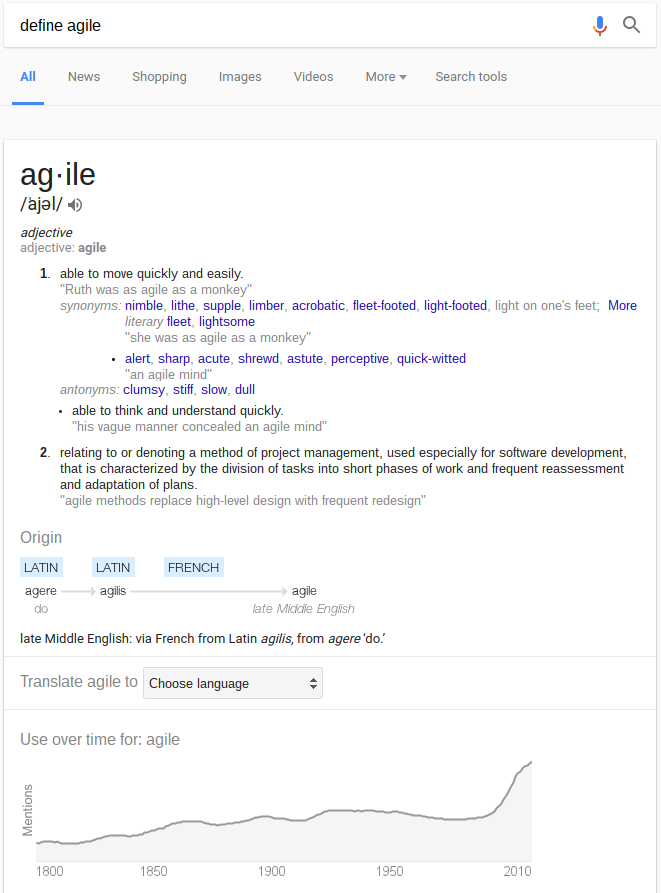

Agile: the ability to move quickly and easily.

A question worth considering is, ‘Are our schools agile enough to evolve with society?’

Do they move quickly and easily, with clear purpose? Or are they clumsy, stiff, and slow?

Most importantly, are they responsive to changes happening in society? If so, how responsive are they, and in what way?

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus once said ‘Everything flows and nothing stays’ — a striking reminder that the only guarantee in our complex world is that change is constant. In modern society, change is occurring all around us, at a seemingly exponential rate. In particular, technology has changed the way in which we live, work, play, and socialise. Yet at times, it seems that our schools are stagnant, unresponsive, and unwilling to adapt, reinvent, and reimagine learning opportunities in order to stay relevant.

‘Agile’ as defined by a Google search. Interestingly, its use over time shows a significant spike just before the turn of the 21st century.

Let’s rewind only a modest 10 years ago. No iPhone existed, nor did any iPad. Instagram was unheard of, and Facebook had a mere 12 million users.

Fast forward to today, and it’s hard to argue that technology hasn’t fundamentally shifted our world as we know it.

But has technology pervaded our schools in the same way that it has augmented our lives? To a degree it has, in scattered classrooms, with teachers and leaders who recognise the potentials and pitfalls of technology, and are agile enough to adapt.

Has technology pervaded into every classroom, or has every teacher changed their processes and structure in response to technology? Not a chance.

Our ignorant inheritance

Today we live in an ‘innovation economy’. The skills required to succeed in life have intersected with the skills required to be an effective citizen. Several decades ago, well before teachers and students used the internet, it made a lot of sense to teach the facts and content of a specified curriculum. This ‘factory model’ of education, where the teacher was the ‘dictator’, was acceptable for the time, but bears little relevance for today. However, the influence of an industrial era model can still be observed in schools now.

The tragedy of this inheritance is that we hold a lot of traditional structure that has become engendered in us. Generally speaking, learners are grouped according to age, with the teacher then deciding how to unpack the specified curriculum to those groups of learners. We tend to favour the telling of content to students rather than allowing them to discover. We tend to teach to the cohort rather than personalise pathways. Innovative teaching methods that involve technology such as flipped-classrooms, blended learning, game-based learning, makerspaces, inquiry, and project-based learning are yet to become the ‘norm’ in every school community.

Above all, technology has made access to information ubiquitous. Students no longer have to rely on only the teacher to learn or discover. Yet, the majority of our schooling system reinforces that students should come to school ready to listen and memorise the content from the teacher, or risk a demotivating failure on a test.

There should be no competitive advantage on how much ‘Student A’ may know in comparison to ‘Student B’. Both have, or should have, the commodity of knowledge available to them with the swipe of a finger. Instead, both students need to be able to ask great questions, critically analyse information, form expressive opinions, create products and solutions, and collaborate and communicate with one another, with and without technology. These are the skills essential for life in today’s world.

Essentially, school as we knew it, depended on how well pupils could passively consumecontent and retain facts and knowledge from the teacher, assessed by what students knew. School as we need to know it, should depend on how well pupils can actively consume then create content, critically ascertain facts from multiple sources, and be assessed with what students do with what they know.

So we need to ask ourselves, are we consciously and actively developing these opportunities with our students in mind? Or are we falling short? As the 2016 education machine turns out the next graduates from a system that teaches and tests narrow aspects of a curriculum that any smartphone can handle, we potentially set our future generations for failure, unhappiness, and social discontent.

We need to face the facts and recognise that technology has caused disruption to our economy and society. However, embracing technology will also be one answer moving forward, with many schools having already done so. Has technology fundamentally changed the machine of education? Not yet… but it certainly has started to put the wheels in motion.

Change in our schools

With the rapid change in the last 10 years, one has to wonder what the next decade will bring. Will schools be responsive enough to meet the needs of today and tomorrow, with one eye on the present and one eye towards the future? Will they be agile enough to remain relevant for students and their parents?

Schools will need to be prepared to change, adapt, and reimagine the established machine of school as we know it.

Change is taxing and requires effort. It requires us to be comfortable with the uncomfortable. It requires us to challenge the status quo, recognising that what we have always done may not be the best solution; and being dissatisfied with ineffective and no longer relevant pedagogies, procedures, and structures. It requires relentless dialogue and shared vision with all stakeholders about the purpose of school, the alignment of our beliefs and practices, and asking the question: ‘is this best for our students right now’?

We have natural a disposition to protect the tried and tested, rather than embracing the ‘new’. This is why new and innovative ideas are difficult to launch and gain traction, as the natural response of the status quo is to favour the known road rather than the risky foreign pathway.

Creating the space for innovative change to occur requires risk, trial and error, and an open mindset. After all, no real learning happens with failure, for either students or teachers. This means schools, leaders, and teachers need to be prepared to try new techniques if we are to disrupt conventional methods of education. We also need to be prepared for the status quo push-back, and allow space for positive conflict, disturbance and uncertainty to occur, in order to find ideas that will provide the highest level of value and outcomes for all stakeholders.

Schools need to create space for innovation, and at times, tolerate the messy and chaotic rather than the predictable and ordered. (Image credit: A photo by Azrul Aziz)

The age of disruption

Examples of disruptive innovation and its impact on society can be observed at an increasing rate, as more and more organisations exploit technology and the consumer. Uber and similar ride-sharing services are changing the way in which we travel, Airbnb is changing the way we sleep abroad, and Google Cars and other autonomous vehicles are changing the way we commute, deliver, and transport goods.

The innovators behind these initiatives have a few things in common:

- They are agile and responsive. They have grown quickly, and have a ‘fail fast, fail quick’ approach to rapidly improve their services.

- They leverage technology to find gaps and meet the needs of clients in new ways.

- They are not afraid to find problems and tackle them head on.

Schools could probably learn a lot learn from these examples!

American businessman Jack Welch once said: “If the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, the end is near”. As tomorrow comes around, current and future technology trends will continue to push the boundaries of traditional schooling.

Can schools keep up with the pace of change on the ‘outside’? (Image credit: A photo by Tim Gouw)

Responding to these trends will be crucial for schools. They may struggle or embrace, dissolve or evolve with society. Those schools that are not agile or responsive may eventually be scrutinised by society. It is possible that we could see the whole notion of school questioned, and formal education challenged.

A useful resource for schools and teachers alike is the NMC Horizon Report, which discusses developments in technology, short to long term trends in education, and the associated challenges for schools. It is essential reading and research for any educator who wishes to stay abreast of the influences that will drive educational change and policy.

Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V., and Freeman, A. (2015). NMC Horizon Report: 2015 K-12 Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium. Available from http://cdn.nmc.org/media/2015-nmc-horizon-report-k12-EN.pdf

There are no easy answers available to shift schools in the right direction. The ‘right direction’ will need to be determined by the schools themselves, who will write their own futures. It is reliant upon the stakeholders within school communities to acknowledge the need to take appropriate action. The obvious stakeholders who wield the heaviest axe are teachers and staff leaders.

It is up to us to challenge ourselves to embrace change, so that we might evolve education to a rate that reflects evolution in the society in which we live.

It is up to us to challenge ourselves to let go of the past, recognising that it’s not about what we know from past experiences; but about being open to what could be, and what might better suit the needs of young people today.

Every decision we make contributes to this. When we teach in a certain way, question a traditional paradigm, leverage technology to new potentials, nudge a school in one direction, or influence today’s generation, we co-create what is coming next. It is up to us to be responsive. If we are passive, we will be too late. We can make change happen. We are all, each of us, practising futurists and world-makers. Let’s do so with open eyes, hearts, and minds.

Let’s think differently, learn differently, and disrupt the machine of education as we know it.

It’s up to us to define our own relevant futures.